‘Stuart Sutcliffe is Rock ‘n Roll’ – John Lennon

Stuart Sutcliffe (June 23rd 1940 – April 10th 1962):

Yea Yea Yea

Was curated by Richard Prince

August 10 – October 14, 2013

Harper’s Books presented an exhibition of twenty-one paintings and works on paper by British artist Stuart Sutcliffe (1940–1962). Curated by Richard Prince, Stuart Sutcliffe: Yea Yea Yea marked the artist’s first U.S. retrospective since 2001. the text below is reproduced courtesy of Pauline Sutcliffe and Harpers Books:

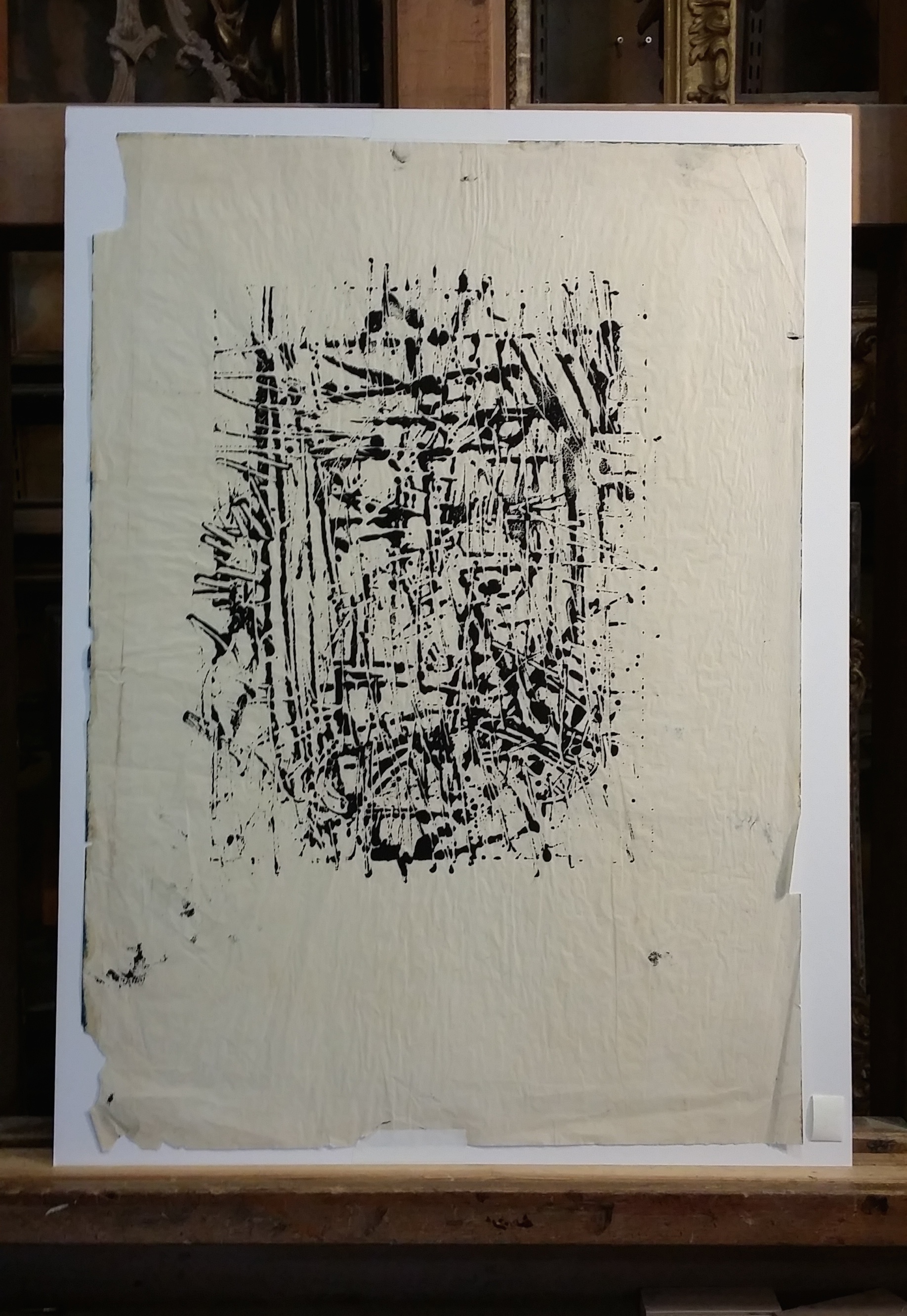

‘The subject of numerous international shows and much critical acclaim, these pieces signal the apotheosis of Sutcliffe’s late style, emphasizing his movement away from figuration into the collaged geometricism of his works on paper and the dense gestural abstraction of his paintings.

Although his legacy is most often overshadowed by his brief membership in an early lineup of The Beatles, Sutcliffe was recognized during his lifetime as a fount of incipient artistic potential, exhibiting at The Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool and participating in the John Moores Biennial while still a teenager. He was accepted into The Liverpool Regional College of Art at the age of sixteen and later attended Hamburg’s Hochschule für Bildende Künste under the tutelage of Pop artist Eduardo Paolozzi, who recognized his unbridled creative talent and exceptional promise early on.

In the years between 1957 and 1960, Sutcliffe met and befriended fellow art school student John Lennon, bought a bass guitar at John’s urging with proceeds from the sale of one of his paintings to John Moores, and joined The Beatles, playing a formative role in the emerging band’s style and artistic direction. After a series of exhaustive all-night stints during the group’s notorious Hamburg tour, Sutcliffe abandoned his nascent musical career to pursue art full time. Moving in with his fiancée, the photographer Astrid Kirchherr, he immersed himself in the arts, working unremittingly on his canvases until his sudden and unexpected death at the age of twenty-one.

Whereas Sutcliffe’s brief life and career have been documented extensively in films, plays, books, and cultural lore, this exhibition seeks to recontextualize his oeuvre within the paradigm of the contemporary art world, highlighting the enduring significance of his work for both late Modernist art history and present-day artistic practices. Rather than consider what could have happened had he lived beyond his early twenties, Stuart Sutcliffe: Yea Yea Yea focuses on the impressive body of work he left behind, while examining its continued import and influence.

Informed by the context of postwar England and Germany, Sutcliffe’s paintings, lithographs, and collages grapple with issues of representation while bringing, as critic Donald Kuspit notes, a renewed freshness to European permutations of Abstract Expressionism. Half a century after his death, his raw energy and nuanced approach to multimedia composition continue to resonate with audiences, cementing his place as a seminal figure within the broader spectrum of late twentieth century art. Richard Prince’s curation and accompanying text further evince the timelessly visceral impact of Sutcliffe’s aesthetic and its abiding relevance for artists working today.

The exhibition is accompanied by a limited edition booklet featuring an essay by Richard Prince, reproduced below, and published by Harper’s Books. Of an edition of five hundred copies, fifty are signed by Richard Prince and Stuart’s sister Pauline, and five will include original artwork by Prince. In addition to the twenty-one works on display, highlights from the Stuart Sutcliffe archive are exhibited in vitrines around the gallery. Providing insight into the working process, intellect, and development of the artist, the collection included notebooks, sketches, correspondences, essays, and photographs, mostly from the years between 1956 and 1962. All images are provided courtesy of The Stuart Sutcliffe Estate.

For more information, please contact Harper Levine at (631) 324-1131 or [email protected].

Yea Yea Yea

An Essay by Richard Prince

Yea Yea Yea.

How do you talk about an artist who died just as he was getting ready. Who was already there. (Not on his way but arrived.) And then just like that, some unforeseen medical condition zapped him and cut him down. Dead at 21. This is what happened to Stu Sutcliffe.

Right next to it.

I first saw Sutcliffe’s paintings on TV. It was a documentary about his life. In the doc his sister was standing in front of three of his paintings talking about her brother. I stared at the paintings behind her. I liked what I saw and I said to myself some day I’d like to visit her and see them for myself, in person. They were monochromatic black paintings and reminded me of a style of abstract work that came out of the Pacific Northwest in the late fifties. I was thinking Mark Tobey. I wasn’t sure this reaction was even true. It was a guess. But even thru the filter of the TV I could tell they were intelligent, steady, right, solid. At least that’s what I remember. The paintings looked like the guy knew what he was doing. He had figured out a way to make an abstract painting all over again.

Spellbound.

Twenty years later my wish came true. I found myself standing in the basement of a house in Wainscott, NY, north of the highway, that belonged to Pauline Sutcliffe, Stu’s sister. Harper Levine had hooked us up and there I was… excited as hell to be able to see them live. I couldn’t believe it. Wainscott. Really? I have a house in Wainscott. Stu’s sister was right across the street living with her brother’s beautiful paintings. What are the chances?

Astronomical.

Sutcliffe was one of the fifth Beatles. The other three being Pete Best, George Martin, and their manager, Brian Epstein. Best is the best-known fifth, but for me Sutcliffe was a whole half.

Should I stay or should I go?

When the Beatles left Hamburg and returned to Liverpool, Sutcliffe stayed on and went with his first truth. He was in love with making art. He wasn’t a musician. It was fun while it lasted but his heart wasn’t in it. Being a Beatle was a crazy scene, but it didn’t make sense, wasn’t the right fit, and the only way for Stu to dial it up was to be on his own in front of canvas, paper, brushes, and paint… in some attic thinking about Henry Moore instead of Chuck Berry.

Just give me some truth.

Stuart was John Lennon’s friend. Maybe his best friend. It was hard to tell Lennon he needed to leave for what he knew to be “the only thing that mattered.”

Paperback Artist.

With help from his Hamburg girlfriend Astrid Kirchherr, Stuart changed the way the band looked. He became the cover boy. (In terms of iconography, if you want to talk about a rock ‘n’ roll trendsetter, you might want to consider Stu’s style and look as a starting point.) Astrid along with Klaus Voorman befriended the band but mostly singled out Stu to hang with when “the boys” weren’t playing six sets a night at the okay corrals in and around the red light district of Hamburg. Astrid cut his hair (got rid of his rockabilly pompadour) and styled his locks into what would eventually become the signature mop-top Beatle haircut. (Moe of The Three Stooges had it first, but not quite as nuanced. And besides, Moe didn’t look like James Dean.)

It’s All Right Ma, I’m only sighing.

Astrid was a photographer and their relationship was perfect. Avant-garde meets a “vicious” bass player… head over heels, each and every hour, not a day goes by… a prelude to Grapefruit. What happened between the two of them was an early version of an Ono “yes.”

This Is The End.

I have some idea of what it’s like to be in a band and not see a future in it. There’s a lot of waiting around and it gets boring and you have to talk to people. It’s “collaborative.” I have no idea what Stuart saw, but most likely he felt restricted, nothing was flowing, everything having to be rehearsed and remembered and having to struggle to keep up, maybe feeling out of it, marginalized, off to the side, a “side kick”… tagging along… going thru the motions, and knowing in the end you’ll never be able experience a spiritual high without the work, the effort, the trying. He wanted his high by himself. And he wanted the high to go all the way.

Funny Face.

It was in the studio, alone, that he was in his skin. Finally comfortable. This is where I belong. It’s easy. And I like a place where I can go to and do and be anything I want. When he split and opened his studio door he was home sweet home.

I can do this all day blindfolded.

(The object of my affection starts to breathe.)

When I was standing in front of those three black paintings at Stuart sister’s in Wainscott I got that feeling. Once in a while it happens. Not as often as I’d like but when it does it’s transformative and sends me to a place that’s glorious and ideal. (I once described the feeling as colossal.) I knew immediately. I was looking at paintings I connected with. That’s as simple as I can say it. Connection. I was in them and they were in me. Sounds corny. (Better cornball than no balls.) I can’t explain it any other way. Fuck it if it doesn’t sound profound. It’s got nothing to do with grammar. I can only tell you it’s a feeling and what I felt was good. The turn on was nice and warm. I was involved. His experience was mine. I felt him starting it, making it, painting it. I knew exactly what he was thinking. We agreed. There was no difference between him and me. For a couple of minutes we were the same person.

Copyright Richard Prince 2013